FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Home > Book of Abraham > Charles Larson's "Restoration" of Facsimile 1 and its Implications for the Book of Abraham

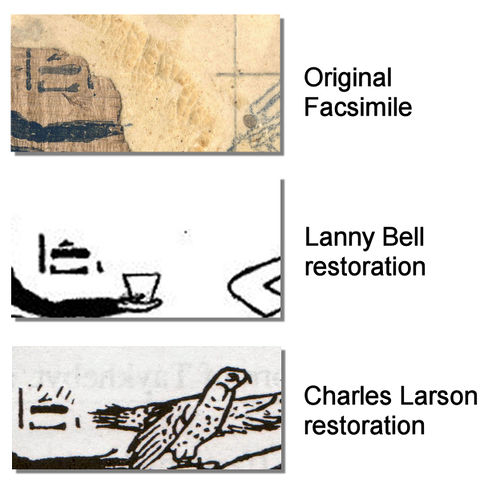

Summary: Charles Larson, a researcher associated with the anti-Latter-day Saint Institute for Religious Research, created a "restoration" of Facsimile 1 of the book of Abraham as part of his 1992 book By His Own Hand upon Papyrus: A New Look at the Joseph Smith Papyri.

The papyrus which contained Facsimile 1 of the book of Abraham was likely damaged after it was translated by Joseph Smith. The original papyrus is mounted on paper and there are pencilled drawings of figures (likely done by Reuben Hedlock) that would become what we see in the Facsimile 1 published in Latter-day Saint scriptures today.

Larson—building off of the suspicions of non-Latter-day Saint Egyptologists like Théodule Devéria, Klaus Baer, Richard Anthony Parker, and Albert Lythgoe—tried to reconstruct the original papyrus that contained Facsimile 1 in an attempt to show that Joseph Smith fabricated the book of Abraham. His restoration contradicts the explanations that Joseph Smith gave of the various figures associated with Facsimile 1.

Here we present Charles Larson's Restoration of Facsimile 1:

Below is the original papyrus that would become Facsimile 1 of the book of Abraham. One can see some pencilled in drawings that roughly correlate with the explanations of the Facsimile given by Joseph Smith:

Finally, here is Facsimile 1 as presumably seen by Joseph Smith and published today in Latter-day Saint scriptures:

The Larson restoration differs from Joseph Smith's explanations in the following ways:

We will examine each of these attempts at restoring the Facsimile below and show how they are faulty or non-probative of anything negative regarding the book of Abraham.

We will use the work of non-Latter-day Saint Egyptologist Lanny Bell to support our case. Bell did his own restoration of the Facsimile and differed in many regards from Larson.

The Larson restoration presumes that the upper hand represented in Facsimile 1 is instead the wing of a bird. There are several elements which disprove this.

Lanny Bell wrote:

Let me state clearly at the outset my conviction that the questionable traces above the head of the Osiris figure are actually the remains of his right hand; in other words, Joseph Smith was correct in his understanding of the drawing at this point. Ashment 1979, pp. 36, 41 (Illustration 13), is very balanced in his analysis of the problem, presenting compelling arguments for reading two hands; Gee 1992, p. 102 and n. 25, refers to Michael Lyon in describing the "thumb stroke" of the upper (right) hand; cf. Gee 2000, pp. 37-38; and Rhodes 2002, p. 19, concludes: "... a careful comparison of the traces with the hand below as well as the tip of the bird's wing to the right makes it quite clear that it is the other hand of the deceased."...An important clue is provided in the orientation of the thumbs of the upraised hands toward the face. This is the expected way of depicting the hands of mourners and others when they are held up to (both sides of) their heads or before their faces.[1]

The head of the priest in the Hedlock restoration appears to simply copy the head of the reclining figure. An examination of the papyrus, however, shows evidence that the head was originally that of Anubis. In this case, the Larson restoration appears to be correct. Theologically, it would not matter to scenes such as this one. Ancient art depcting religious situations such as this frequently had other people impersonating other Gods. Thus, even if this is an incorrect restoration, it would not matter to the overall message of the scene portrayed.

The priest of Elkenah likely could have been wearing an Anubian headdress while performing this scene and the interpretation would still be, for all intents and purposes, correct. Those performing rituals often donned a mask impersonating a particular god for theological effect.[2]

John Gee has written:

The discussion about figure 3 has centered on whether the head should be that of a jackal or a bald man. Whether the head is a jackal or a bald man in no way affects the interpretation of the figure, however, since in either case the figure would be a priest.

His footnote here reads as follows:

The argument for the identification runs as follows:

(2) Assume on the other hand that the head on Facsimile 1 Figure 3 is that of a jackal, as was first suggested by Theodule Devéria. We have representations of priests wearing masks, one example of an actual mask, [and] literary accounts from non-Egyptians about Egyptian priests wearing masks. . . . Thus, however the restoration is made, the individual shown in Facsimile 1 Figure 3 is a priest, and the entire question of which head should be on the figure is moot so far as identifying the figure is concerned. (John Gee, “Abracadabra, Isaac, and Jacob,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 7/1 [1995]: 80–82)[3]

(1) Assume for the sake of argument that the head on Facsimile 1 Figure 3 is correct. What are the implications of the figure being a bald man? Shaving was a common feature of initiation into the priesthood from the Old Kingdom through the Roman period. Since “Complete shaving of the head was another mark of the male Isiac votary and priest” the bald figure would then be a priest.

Gee gives an example of this of a bald priest donning the head of Anubis at the temple of Dendara. The first image is an actual drawing created during the Ptolemaic period from Dendara of the priest putting on the mask. The second is an example of such a mask that would be placed on them.

The Larson restoration adds a phallus on the reclining figure, something that is never seen on a clothed Osiris figure.

Lanny Bell confirmed this understanding:

[T]he representation of an ithyphallic [def.: having an erect phallus] figure wearing a kilt would not be unparalleled. However, judging from the position of the erect phallus of the reclining kilted earth god Geb in a cosmological scene on Dynasty 21 Theban coffins now in Turin and Bristol, there would not be enough available space to restore the hand of Anubis, the erect phallus of the Osiris, and the body and wings of Isis in P.JS I: Anubis would have to be grasping the phallus himself and assisting Isis in alighting on it—which is unimaginable. . . .In this area, I believe the Parker-Baer-Ashment reconstruction (with its "implied" erect phallus) is seriously flawed.[4]

Since Facsimile 1 appears to be a fairly typical scene from Egyptian funerary texts, it is noted that other similar Egyptian motifs do not show the priest holding a knife. Lanny Bell, for example, shows the priest holding a cup in his hand over the figure on the lion couch and Larson proposes that a second bird was being gestured to.

However, it is not possible through an examination of the original papyrus to determine what the priest is holding in his hand.

Many Latter-day Saint scholars believe that the scroll was damaged after Joseph translated the vignette and some evidence seems to support this view. One early Latter-day Saint who saw the papyri in 1841, for instance, described them as containing the scene of an altar with "'a man bound and laid thereon, and a Priest with a knife in his hand, standing at the foot, with a dove over the person bound on the Altar with several Idol gods standing around it.'"[5] Similarly, Reverend Henry Caswall, who visited Nauvoo in April 1842, had a chance to see some of the Egyptian papyri. Caswall, who was hostile to the Saints, described Facsimile 1 as having a "'man standing by him with a drawn knife.'"[6]

Notes

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now