FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

A personal favourite of mine is Belgian painter Pierre Bruegel the Elder. In his "Census of Bethlehem," (1569), he turns Bethlehem into a Renaissance Belgian village! | A personal favourite of mine is Belgian painter Pierre Bruegel the Elder. In his "Census of Bethlehem," (1569), he turns Bethlehem into a Renaissance Belgian village! | ||

[[Image:BRUEGEL Le dénombrement de Bethléem.png | [[Image:BRUEGEL Le dénombrement de Bethléem.png]] | ||

The snow is the first tip-off that all is not historically accurate, but the skaters on the pond, the clothing, and the houses are all wrong. Was Bruegel trying to perpetuate a fraud? Or, did he have something else in mind? | The snow is the first tip-off that all is not historically accurate, but the skaters on the pond, the clothing, and the houses are all wrong. Was Bruegel trying to perpetuate a fraud? Or, did he have something else in mind? | ||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

An Italian work from the 13th century gives us "The Nativity with Six Dominican Monks," (1275). | An Italian work from the 13th century gives us "The Nativity with Six Dominican Monks," (1275). | ||

[[Image:Nativity with 6 Dominicans.png | [[Image:Nativity with 6 Dominicans.png]] | ||

Yet, there were surely no monks at the Nativity, and the Dominican order would not be formed until the early 13th century. Was this merely an attempt to "back-date" the order's creation, giving them more prestige? | Yet, there were surely no monks at the Nativity, and the Dominican order would not be formed until the early 13th century. Was this merely an attempt to "back-date" the order's creation, giving them more prestige? | ||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

Even details of no religious consequence are fair game for our artists to get "wrong." Giovanni Bellini's portrait of Mary might seem innocuous enough, until one spots the European castle on the portrait's right, and the thriving Renaissance town on the left. | Even details of no religious consequence are fair game for our artists to get "wrong." Giovanni Bellini's portrait of Mary might seem innocuous enough, until one spots the European castle on the portrait's right, and the thriving Renaissance town on the left. | ||

[[Image:Bellini Madonna 1.png| | [[Image:Bellini Madonna 1.png|right]] | ||

===Non-European cultures=== | ===Non-European cultures=== | ||

Other cultures follow the same pattern. Korean and Indian artists portray the birth in Bethlehem in their own culture and dress. Are we to believe (as with Bruegel the Elder) that the artists hope we will be tricked into believing that Jesus' birth took place in a snow-drenched Korean countryside, while shepherds in Indian costume greeted a sari-wearing Mary with no need for a stable at all under the warm Indian sky? | Other cultures follow the same pattern. Korean and Indian artists portray the birth in Bethlehem in their own culture and dress. Are we to believe (as with Bruegel the Elder) that the artists hope we will be tricked into believing that Jesus' birth took place in a snow-drenched Korean countryside, while shepherds in Indian costume greeted a sari-wearing Mary with no need for a stable at all under the warm Indian sky? | ||

<center> | |||

[[Image:Korean Nativity 1.png| | [[Image:Korean Nativity 1.png|Korean Nativity 1.png]] | ||

[[Image:Indian Nativity 1.png| | [[Image:Indian Nativity 1.png|Indian Nativity 1.png]] | ||

</center> | |||

===African example=== | ===African example=== | ||

For a final example, consider an African rendition of the Nativity, which shows Mary in traditional African costume. All have African features: | For a final example, consider an African rendition of the Nativity, which shows Mary in traditional African costume. All have African features: | ||

<center> | |||

[[Image:Jesus mafa 1.png|frame|left|CAPTION]] | [[Image:Jesus mafa 1.png|frame|left|CAPTION]] | ||

</center> | |||

Surely this goes beyond the bounds of acceptable artistic license? Isn't it possible that a somewhat naïve African villager might think that Jesus was born in Nairobi, instead of Palestine? | Surely this goes beyond the bounds of acceptable artistic license? Isn't it possible that a somewhat naïve African villager might think that Jesus was born in Nairobi, instead of Palestine? | ||

One of the strangest attacks on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is an assault—of all things—on the Church's art. Now and again, one hears criticism about the representational images which the Church uses in lesson manuals and magazines to illustrate some of the foundational events of Church history.[2]

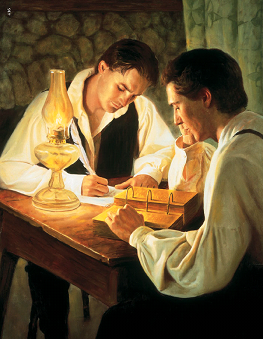

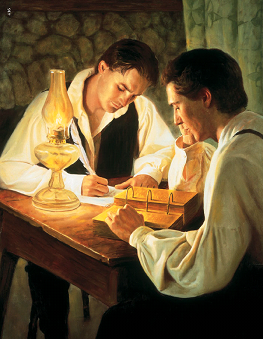

A common complaint is that Church materials usually show Joseph translating the Book of Mormon by looking at the golden plates, such as in the photo shown here.

Here critics charge a clear case of duplicity—Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith are shown translating the Book of Mormon.

But, as the critics are quick to point out, there are potential historical errors in this image:

So, are the Church's artistic department or artists merely tools in a slick propaganda campaign? Is the Church trying to "hide" how Joseph really translated the plates?

If the Church is trying to hide these facts, it does a poor job of it.

The manner of the translation is described repeatedly, for example, in the Church's official magazine for English-speaking adults, the Ensign. Richard Lloyd Anderson discussed the "stone in the hat" matter in 1977,[3] and Elder Russell M. Nelson quoted David Whitmer's account to new mission presidents in 1992.[4]

The details of the translation are not certain, and the witnesses do not all agree in every particular. However, Joseph's seer stone in the hat was also discussed by, among others: B.H. Roberts in his New Witnesses for God (1895)[5] and Comprehensive History of the Church (1912),[6] The Improvement Era (1939),[7] BYU Studies (1984, 1990)[8] the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (1993),[9] and the FARMS Review (1994).[10] LDS authors Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler mentioned the matter in 2000.[11]

Elder Neal A. Maxwell went so far as to use Joseph's hat as a parable; this is hardly the act of someone trying to "hide the truth":

Critics who attack the Church based on its artwork should perhaps take Elder Maxwell's caution to heart.

Why, then, does the art not match details which have been repeatedly spelled out in LDS publications?

The simplest answer may be that artists simply don't always get such matters right. The critics' caricature to the contrary, not every aspect of such things is "correlated." Robert J. Matthews of BYU was interviewed by the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, and described the difficulties in getting art "right":

Modern audiences—especially those looking to find fault—have, in a sense, been spoiled by photography. We are accustomed to having images describe how things "really" were. We would be outraged if someone doctored a photo to change its content. This largely unconscious tendency may lead us to expect too much of artists, whose gifts and talents may lie in areas unrelated to textual criticism and the fine details of Church history.

Even this does not tell the whole story. "Every artist," said Henry Ward Beecher, "dips his brush in his own soul, and paints his own nature into his pictures."[14] This is perhaps nowhere more true than in religious art, where the goal is not so much to convey facts or historical detail, as it is to convey a religious message and sentiment. A picture often is worth a thousand words, and artists often seek to have their audience identify personally with the subject. The goal of religious art is not to alienate the viewer, but to draw him or her in.

The critics would benefit from even a cursory tour through religious art. Let us consider, for example, one of the most well-known stories in Christendom: the Nativity of Christ. How have religious artists portrayed this scene?

A personal favourite of mine is Belgian painter Pierre Bruegel the Elder. In his "Census of Bethlehem," (1569), he turns Bethlehem into a Renaissance Belgian village!

The snow is the first tip-off that all is not historically accurate, but the skaters on the pond, the clothing, and the houses are all wrong. Was Bruegel trying to perpetuate a fraud? Or, did he have something else in mind?

An Italian work from the 13th century gives us "The Nativity with Six Dominican Monks," (1275).

Yet, there were surely no monks at the Nativity, and the Dominican order would not be formed until the early 13th century. Was this merely an attempt to "back-date" the order's creation, giving them more prestige?

Even details of no religious consequence are fair game for our artists to get "wrong." Giovanni Bellini's portrait of Mary might seem innocuous enough, until one spots the European castle on the portrait's right, and the thriving Renaissance town on the left.

Other cultures follow the same pattern. Korean and Indian artists portray the birth in Bethlehem in their own culture and dress. Are we to believe (as with Bruegel the Elder) that the artists hope we will be tricked into believing that Jesus' birth took place in a snow-drenched Korean countryside, while shepherds in Indian costume greeted a sari-wearing Mary with no need for a stable at all under the warm Indian sky?

For a final example, consider an African rendition of the Nativity, which shows Mary in traditional African costume. All have African features:

Surely this goes beyond the bounds of acceptable artistic license? Isn't it possible that a somewhat naïve African villager might think that Jesus was born in Nairobi, instead of Palestine?

As the director of Catholic schools in Yaounde, Cameroon argues:

The goal of religious art is primarily to convey a message. It uses the historical reality of religious events as a means, not an end.

Religious art—in all traditions—is intended, above all, to draw the worshipper into a separate world, where mundane things and events become charged with eternal import. Some dictated words or a baby in a stable become more real, more vital when they are connected recognizably to one's own world, time, and place.

This cannot happen, however, if the image's novelty provides too much of a challenge to the viewer's culture or expectations. And the critics know this. They are counting on it.

What religious message(s) does the Del Parson translation picture convey?

It is, I suspect, this last point that makes the critics cry "foul." They don't want the seer stone in the hat to be well-known because this actually makes it harder for Joseph to cheat. They aren't even worried about historical accuracy—they're happy to downplay the impressive witness testimonies of the plates' reality. Nor is a seer stone in a hat intrinsically less plausible than a Urim and Thummim with breastplate.

No, what the critics want is to make the translation alienating. They want it to seem bizarre, even eerie. They hope that a historical truth in visual form will allow them to slip a bigger lie by us.

They want a portrait of the translation that will convey something to a modern audience that it never portrayed to the participants—that the Book of Mormon was uninspired and uninspiring.

Come to think of it, perhaps this attack isn't so strange after all.

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now